VC tension: gaining confidence with the non-consensus

After almost a year after switching to the investing side, I've been thinking more critically about my investment mindset. It drove me to write this calibration post a few weeks back.

As I shared, early-stage venture is "a never-ending calibration exercise." My takeaway was that it's time to tweak my thinking:

- From: that seems like a safe bet.

- To: the odds may not be in our favor, but holy shit, what if this thing actually works out?

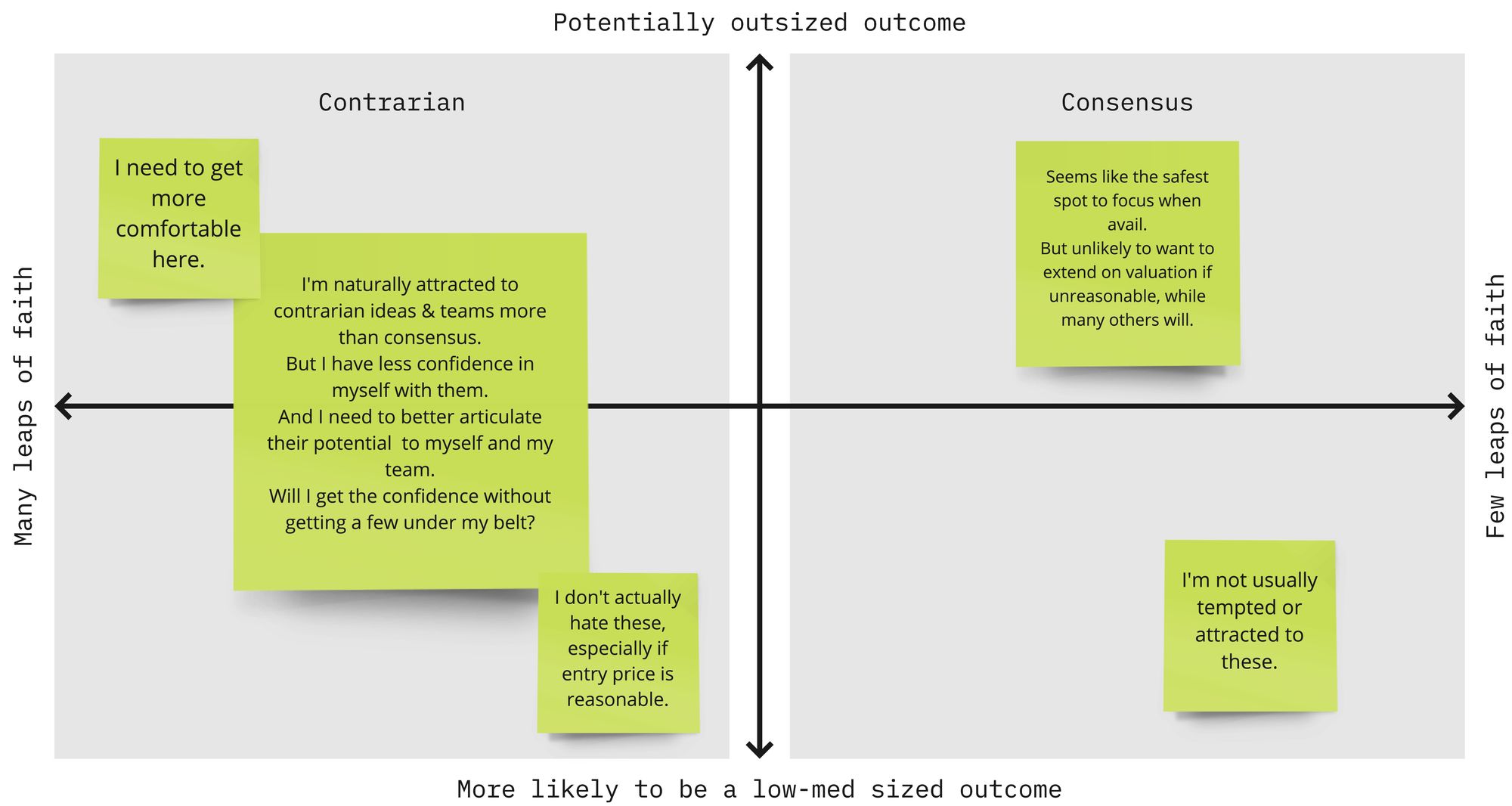

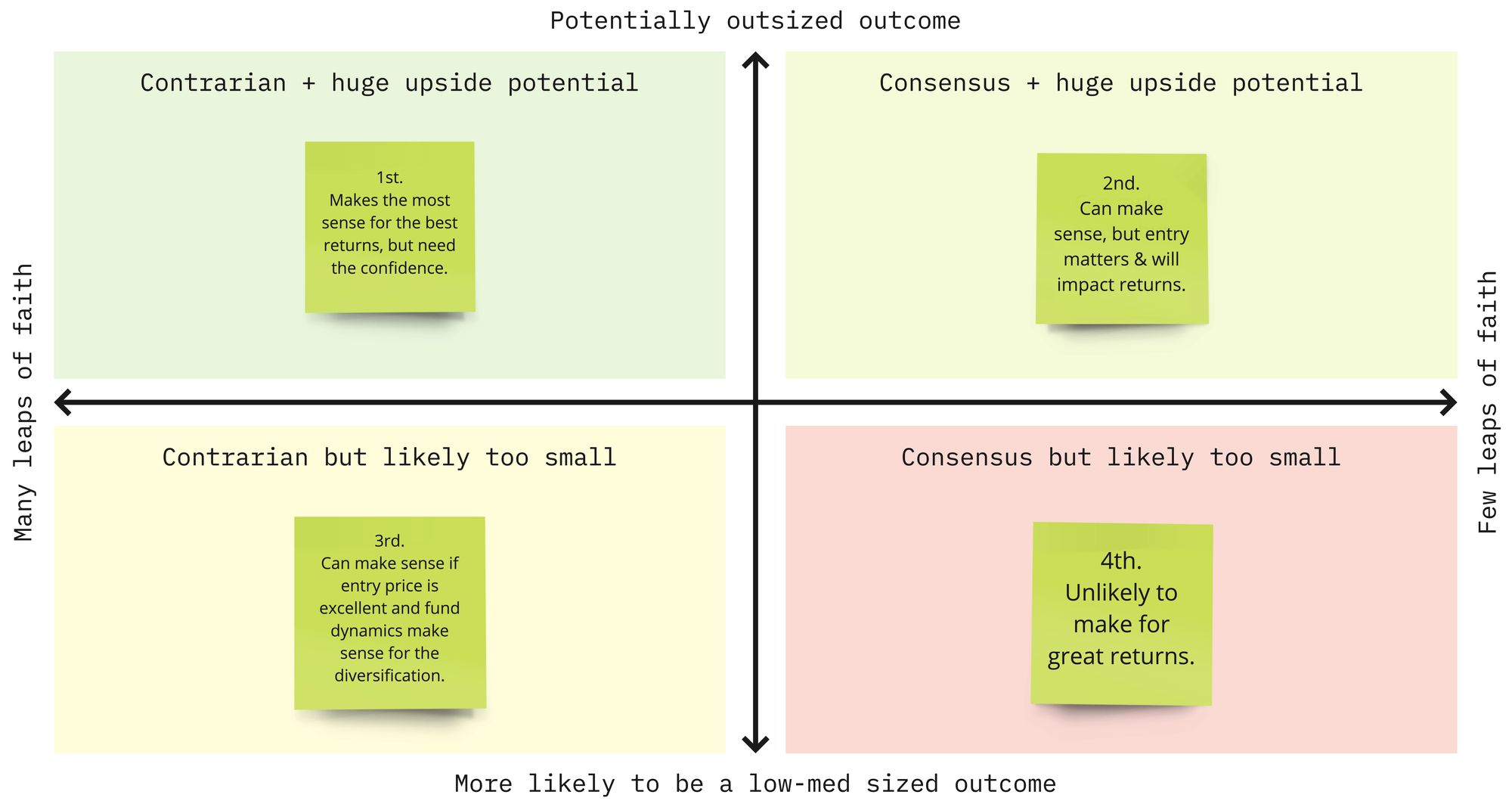

After that post, I drew a simple 2x2 on my whiteboard that I've been staring at ever since to help me figure out this game, and figure out myself. Here's a digital version:

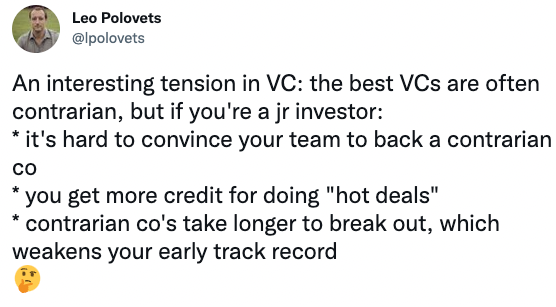

And then yesterday, I saw this tweet from Leo at Susa Ventures.

So I figured I'd jot down a few quick thoughts since this has been on my mind.

- What do I mean by contrarian vs. consensus? Simply those opportunities where few, if any, other investors like it. Maybe the team is atypical, the product seems super original or perhaps crazy, or the space isn't usually considered desirable. It requires thinking for yourself.

...independent-mindedness.... It seems to me that it has three components: fastidiousness about truth, resistance to being told what to think, and curiosity.

- There's a fine line between being a contrarian and just picking a loser. Losing haunts you. Losses early on and you're probably done. It's scary. If you're wrong, even for different reasons than everyone originally expected, you're still wrong.

- I'm new to venture, but I'm old[er] (35yo in a land seemingly filled with many much younger). I don't just want to put short-term points on the board to advance my career. I want to find great investment opportunities for us to lead and help a few great companies a year. I want each to have the potential to return the fund. But that will likely mean the founder(s) and business are relatively contrarian. Contrarian deals have less competition from investors, less competition in the field, and market creation opportunities. But they're scarier and riskier, with a likelihood of completely failing. As Leo said, they can take much longer to break out. It can be tougher for them to raise follow-on financing, especially if the perceived outcome will be bounded. The more startup miracles required, the more likely it is to fail. Failure is generally bad. As a newer investor, Leo highlights how one can be driven to put points on the board to increase chances of getting deals done. But they can come at the expense of those with great return profiles. Newer investors are generally less likely to do contrarian deals than consensus.

- It helps to remember markets are generally bigger than ever before, and can often become bigger than you'd generally think, when you’ve done the work to believe it can be 'big.'

Investors are just people. We're trying to do our best and figure it out as we go, just like most entrepreneurs. Most are mediocre at this job. Few are exceptional.

Careers are defined, and funds are returned in the top left quadrant. Some younger investors may hang there, but many won't for the reasons Leo highlighted. Most will move that direction over time, after playing it safe and earning their way. Only those proven to be the best can really pull off keeping it simple with new, original, complex spaces.

He hit on a genuine tension. Every [newer] investor needs to figure out how to best navigate their career and day-to-day decisions best.

As for me, I'll keep calibrating and coming back to posts like this as I try to hone the craft of being a great picker. Ultimately, here's the question I'm trying to figure out – should we invest in this startup to get a lot of ownership because it can become a really great company? Information is always imperfect.